5th Bomb Squadron

|

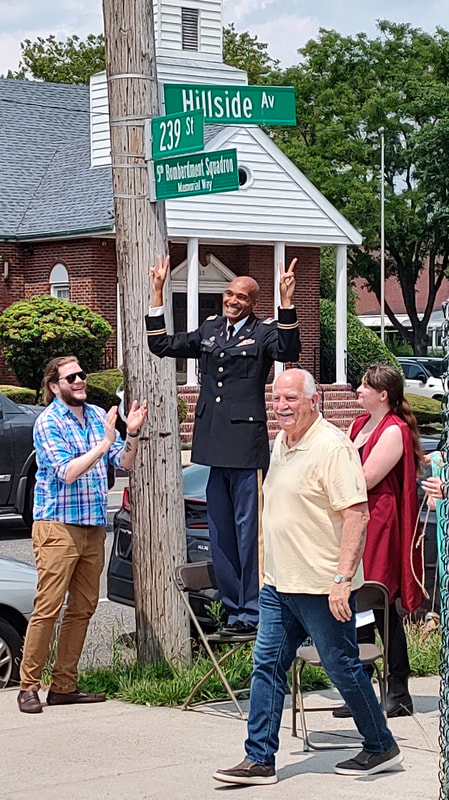

June 17, 2023: 5th Bomb Squadron Memorial Dedication, Bellerose, Queens, NY

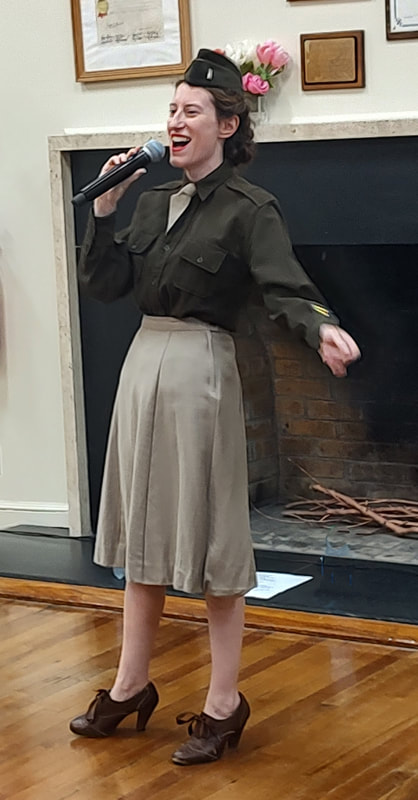

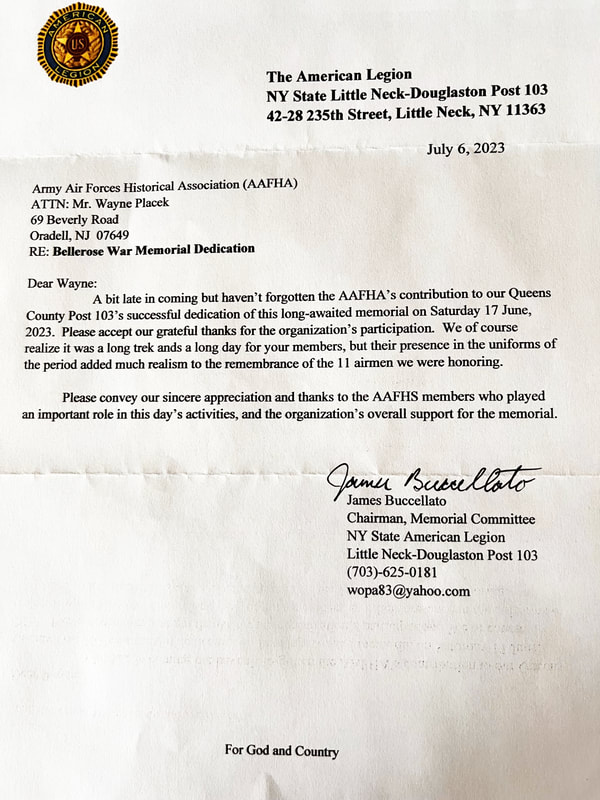

AAFHA was honored to participate in the 5th Bomb Squadron Memorial Dedication. Huge commendation to Jim Buccellato and American Legion Post 103 for initiating and completing the 5th Bomb Squadron Memorial at the corner of 239th Street and Hillside Avenue in Bellerose Queens on June 17. A fantastic ceremony held on a beautiful June Sunday completed the project. Close to 50 family members of the fallen airmen and one civilian came to the site for the dedication ceremony. Alyssa Martin sung the NA and Jim's daughter and son in law Krista and Adam sung "I'll remember You" by the D-Day Darlings and "America the Beautiful" I gave the keynote historical address and a brief walking tour of the crash sites for the families. An incredible reception at the old MF Officer's Club took place following the ceremony with songs by Alyssa and Krista and Adam's, Creedence Clearwater Remix. Members of American Legion Post 103, our Army Air Forces Historical Association, active duty military and 100's of general public also attended the ceremony. What an incredible day. Remember, Respect and Honor!

Above: AAFHA Members at the Mitchel Field Officers Club.

Photos below by Paul Martin: Click on each to enlarge.

|

1. Welcome, Introduction and Invocation.

AL 103, Committee Chairman, Jim Buccellato 7:33 |

2. Pledge of Allegiance, Jim Buccellato.

National Anthem, AAFHA's Alyssa Martin 3:15 |

3. Keynote Historical Address.

AAFHA, and SAL Sq. 1009 member, Paul R. Martin III 22:25 |

|

4. Monument creation remarks.

Jim Buccella 15:42 |

5. Street sign unveiling. Monument Dedication and Flag raising, Jim Buccellato. Taps, "I'll Remember You", Adam and Krista. 10:19

|

6. Thank Yous, Conclusion, Jim Buccellato.

"America the Beautiful" Adam and Krista: 4:44 |

|

|

|

|

An incredible reception at the old MF Officer's Club took place following the ceremony with songs by Alyssa and Krista and Adam's, Creedence Clearwater Remix. Members of American Legion Post 103, our Army Air Forces Historical Association, active duty military and 100's of general public also attended the ceremony. What an incredible day. Remember, Respect and Honor!

Alyssa Martin performing as Dawn O'Day performing at the Mitchel Field Officers Club.

|

Part 1. 14:23

|

Part 2. 14:35

|

Creedence Clearwater Remix performing at the Mitchel Field Officers Club.

|

Part 1. 16:57

|

Part 2. 15:22

|

Part 3. 18:10

|

For over 20 years, AAFHA has been remembering and honoring the history of WWII aviation. We paticipate in public forums and airshows like MAAM WWII Weekend in Reading PA, Open House Airshows at McGuire AFB, and our "Hometown" Airshow at the Greenwood Lake Airport. We march in the Riveredge July 4th Parade and the Sgt. John Basilone Parade in Raritan, NJ, and participate in local Pearl Harbor Commemorations. Our private member only events include our Annual Dinner Dance and Picatinny Luncheon.

|

The Worst in Air Corps and Mitchel Field History

“Like ducks shot out of a flight.” On This day in Mitchel Field History, June 17, 1940. An excerpt from my forthcoming book: Beneath The Shadow of Wings Untold Stories from Mitchel Field, Long Island Volume IV- 1939-1941 The Gathering Storm: by PAUL R. MARTIN III Copyright 2021 by Paul R. Martin III No portion or photos may be reproduced without express written permission of the author. With the potential for global conflict on the horizon in mid-1940, congress began addressing the long neglected and undermanned military service branches with new defense spending bills to expand and equip the Air Corps with updated and more modern aircraft. Meanwhile, pre-draft, all-volunteer aircrews trained almost daily in existing aircraft like the B-18 bomber, already considered obsolete. Eighty new officers who just completed nine months training at Kelly and Randolph Fields in Texas received “final polish as bomber pilots at Mitchel Field, L. I.” (NYHT, June 16, 1940) A B-18 on the tarmac at Mitchel Field. Photo courtesy COAM. “Every day that the weather is favorable the young officers go aloft with more experienced comrades to observe and practice the details of piloting one of the huge silver-hulled bombers assigned to the Field. For ten hours or so they watch the co-pilot perform... Then they move into the co-pilots seat and go through such activities themselves.” (NYHT, June 16, 1940) Designed from the successful DC-2 and DC-3 in 1934, the twin engine B-18 went into production in 1936 and arrived at Army Airfields in 1937. The shark nosed B-18A variant had a top speed of 215 mph but cruised at only 165 with a two-ton bomb load and 3-defensive .30 caliber machine guns. It was 57 feet 10 inches long with an 89.5-foot wingspan. It was later called the “bolo” and because of its appearance, often referred to as the “flying whale”. Air Corps officials immediately recognized it was ill equipped and completely unsuited for the long-range bombing role for which it was designed and acquired. While awaiting increased production of the promising four engine Boeing B-17 (only 155 of which were produced between January 1937 and November of 1941) and its sister ship, the Consolidated B-24, the twin engine B-18, despite its well-known deficiencies, fulfilled the stop-gap role in most Air Corps’ front line operational bomber groups and squadrons. General Arnold described the B-18 in an assessment of all front-line aircraft from a speech he gave at the United States Military Academy in September 1941. A condensed version was printed in the November 1941 issue of The Air Forces Newsletter, headlined “B-18s easy to hit”. “The bulk of our bombardment squadrons were equipped with B-18s, a sitting target for even the slowest of our pursuit planes, and underpowered and slow. They were duds on every count except training, where they were a life saver.” (AFNL, November 1941) The newly arrived pilots were required to co-pilot for a year, amassing 700 hours in the air before promotion to pilot. Their course work included ground school and in flight, radio, navigation, meteorology, and machine gun firing as well as formation flying. Four of the silver, Douglas B-18As from the 5th Squadron of the 9th Bombardment Group lifted off the runways of Mitchel Field at 8:15 June 17, 1940 for a tactical training flight and formation flying exercise; routine work for “reserve officers who had completed their primary flight training at Kelly Field, Texas.” (BDE, June 18, 1940) |

A B-18 on the Mitchel Field runway. Author's collection.

A Douglas B-18A flying over the 1939 Worlds Fair Grounds, not far from Bellerose. LaGuardia Airport is in the center background 1939, Photo courtesy COAM

Several Mitchel B-18As in formation flight. Note the B-18 A "Shark nose" variation. Photo courtesy COAM.

A Mitchel B-18A in flight. Note the B-18 A "Shark nose" variation. Photo courtesy COAM.

|

At 2500 feet above Long Island, they flew in echelon in a diamond-shaped formation, staggered at slightly different altitudes to practice aerial combat maneuvers. They soared at 140 mph in a southwesterly direction above Bellerose Manor, a quiet residential neighborhood along the Nassau/Queens border. “The early morning sun glinted from their silver wings. The thunder of their motors filled the air with sound.” (NYT, June 18, 1940)

Flight leader, 31-year-old Lieutenant and USMA Graduate (Class of 1934) Paul Burlingame, Jr., (see also, 1939, Chapter 2) was the only regular officer among the six on the two craft, the other five were all reserve officers, called to active duty after the national defense emergency was declared in 1939. Burlingame flew on the left side of the formation in B-18-A-9-B-45 (37-576). He radioed the formation and ordered diamond point leader, Lieutenant Richard. M. Bylander, 25, (see also 1939, Chapter 2) piloting B-18-A-9B-43 (37-583), to slide back to the left-wing position and for Lieutenant Leroy Stefanovics to assume the lead role.

The front three planes flew in a V formation with the fourth craft about 300 yards behind. As Bylander descended and slid back and under Burlingame’s ship, their two craft inexplicably collided, locked wings for a moment and then exploded in flames before separating and falling uncontrollably earthward. “There was a ball of flame, then smoke, and the two planes fluttered to the ground like ducks shot out of a flight.” (NYT, June 18, 1940)

Lieutenant James O. Ellis in the rear plane, “heard Burlingame’s order and was about to rejoin the formation when he saw one plane come up under the other and strike it just aft of amidships.” Ellis pulled into a steep climb to avoid crashing into the two planes. “The two machines fell, glued together, for several hundred feet before breaking apart and bursting into flames.” (Hartford Courant, June 18, 1940)

Many people on the ground, although used to the drone of aircraft from Mitchel and Roosevelt Fields and nearby New York Municipal Airport-LaGuardia Field, glanced skyward as the formation passed overhead just before 9 AM.

Mrs. Mary Altekamp looked up. “The two middle planes seemed to crash together and start falling in flames toward the earth.” (BDE, June 17, 1940) Queens Precinct Patrolman William R. Koopman saw the two planes collide and fall in a sharp spin. A kneeling Mrs. Ida Smith planted flowers in her backyard at 241-20 87th Avenue. Attracted by the deafening sound of shrieking metal, she arose to see one of the planes screaming down in a death spiral. “I thought he was doing tricks” she said. Smith warned her next-door neighbor, Mrs. Elsie Gustafson. “Run! They’re coming down!” (NYT, June 18, 1940) Gustafson observed the two planes appear to turn over and suddenly fall earthward in a fatal plunge toward the unsuspecting community below. “From then until the moment they struck the ground, each of the ill-fated planes appeared like a meteorite shooting earthward.” (BDE, June 18,1940)

|

“In a few moments, heavy parts of the wrecked machines began falling upon houses and into the streets, areaways and backyards.” (BDE, June 17, 1940) “The noise of the crash, the roar of flaming gasoline, and the pillars of black smoke caused consternation over a wide area in Queens...” (NYT, June 18, 1940) Both 24,000-pound planes crashed almost simultaneously. Roofs, trees, and overhead power lines were torn apart as the aircraft struck within 100 yards of each other. Bylander, (43) hit the “mall”, a grass divider island in the middle of 239th Street. Burlingame’s aircraft (45) “buried its nose in the dirt in the front yard of the house occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Richard Rangs at 239-22 87th Avenue.” It “dropped like a flaming meteorite into the yard... and set fire to the houses.” (NYT, June 18, 1940) Mrs. Elise Rangs, alone in her house, was just starting breakfast. “I heard a low-flying plane and went to the front door to look,” said Mrs. Rangs, who then ran out into her back yard. (BDE, June 17, 1940)

Parts of Burlingame’s plane also landed next door to the Rangs, on the Kraft house at 22 87th Avenue, setting it afire too. Residences over a half a block away shook from the impact. “The house trembled, and we thought it was going to collapse,” said Mrs. John White at 05 87th Avenue. Mrs. Kraft was on the second floor when the plane hit, and her entire home became enveloped; “set afire by leaping tongues of flaming gasoline”. (BDE, June 18, 1940) She ran through the inferno with her clothes on fire and out a side door. “The interior of her house was completely gutted by the flames.” (BDE, June 18, 1940) The disaster “brought about an immediate mobilization of available rescue equipment by the police and firemen.” (NYT, June 18, 1940) 105 Precinct Patrolman Peter Kogel reached the scene quickly and smothered Mrs. Kraft with a blanket and applied butter and olive oil from a neighbor to treat the severe burns suffered to most of her body. Kogel placed her in a car or ambulance and rushed her to Creedmoor Hospital in critical condition where doctors performed emergency treatment before transfer to Queens General Hospital. Mrs. Laura Chatterton described the scene as an “inferno” as waves of flame erupted from the Kraft’s house where parts of the bomber sliced through several rooms. “Smoke went up everywhere.” (BDE, June 17, 1940) Joseph Sorgie observed the planes fall from 88th Avenue. “I ran to get out of the way,” he said. “When they crashed everything was noise and smoke.” (BDE, June 17,1940) He assisted others who turned water hoses on the burning houses. “Of the six-man crew of the second plane, three were hurled into the driveway between the two houses in front of the garage, their bodies twisted and broken and their clothes aflame.” (BDE, June 18, 1940) “Neighbors rushed to aid the men who were thrown clear.” (BDE, June 17, 1940) First to arrive and render assistance were Edward McLaughlin and his brother, who saw the crash from in front of his home about a half-mile away in Floral Park and drove to the scene. “There was a garden hose going on one of the lawns.” McLaughlin said. “We grabbed it and turned it on one of the men who was lying against a garage door, his clothing all on fire. Then we turned it toward the plane, but we couldn’t get near enough to do any good. ...Even then it was apparent that the men must be dead.” (NYT, June 18, 1940) Only one-man, Corporal Frank X. Deeley, Burlingame’s radio operator, managed to extricate himself from a falling craft. Desperate to save his life he bailed out, (or was thrown from the plane during the collision) unfortunately it was too low for his chute which was on fire, to fully deploy. He plummeted helplessly and struck the Schwartz’ home at 86-16 239th Street. He crashed at an angle through the roof and kitchen ceiling and out the back door, landing dead on the rear porch. |

The scene at the "Mall' on 239th Street, lower right hand corner and the 87th Ave wreckage in upper left hand corner. Photo courtesy NYT.

The Kraft and Rang houses on 87th Ave.

Photo courtesy COAM . A flaming engine lies in the street. Photo courtesy NYT.

|

|

The Kraft and Rang houses on 87th Ave.

Photo courtesy COAM . Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia surveys the destruction at the scene. Photo courtesy NYT.

|

Arriving firemen and emergency workers found smoke and fires strewn all about the neighborhood. They battled the burning houses and plane and searched for survivors. The airmen crushed inside the crumpled fuselage had little chance to escape. By the time the flames were extinguished, “emergency workers found their broken bodies over a scattered area.” (BDE, June 17, 1940)

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia surveys the destruction at the scene. Photo courtesy NYT.Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia was driven to the scene from his summer “City Hall” at his home in Northport by Police Patrolman Thomas Pugh. “This is one of the inevitable accidents of training.” (BDE, June 17, 1940) The Mayor said when he arrived on scene. It seemed to him that even in the death throes of their final moments alive, the two doomed pilots kept their wits about them and gallantly tried to control their stricken craft to avoid crashing directly into houses. LaGuardia, himself an aviator in the world war, surveyed the destruction and pointed to the clearly marked pathway. “That fellow tried to land. See where he skidded along the road. He did not want to hit those houses.” The Mayor remarked. (NYT, June 18, 1940) The men in the center of the planes were believed to have died instantly, but the pilots and co-pilots, forward of the initial blast “probably remained conscious for a short time, struggling to land the planes in the streets.” (NYDN, June 18, 1940) Officials at Mitchel Field strongly suggested “that the two pilots spent their last moments swinging the crashes away from Bellerose homes.” (NYDN, June 18, 1940) “Had the ships plowed into the two blocks of houses instead of falling into the streets, officials agreed that the wreckage and loss of life might have been considerable.” (NYHT, June 18, 1940) Colonel Douglas Netherwood arrived from the field a short time later to begin an official Army investigation into the cause of the accident that destroyed two $85,000.00 bombers and cost twelve lives. In the afternoon, the bodies of the airmen were taken by ambulance to Jamaica Hospital. Neighbors’ “futile efforts were pitifully evident... one was covered with a woman’s green skirt; the others had scorched blankets over them.” They were all so severely burned that visual recognition was impossible and dental charts were required to ascertain their identities. They were moved to Fliedner Funeral Home in Great Neck pending notification of the families. For several hours, Doctors in Queens County Hospital waged a hopeless fight, exhausting every procedure to save Mrs. Emily Kraft’s life. She succumbed to her burns at 3:40 AM the following day, June 18. Emily, a German immigrant, had sadly only moved into the neighborhood three weeks prior. She left behind her husband Otto and two young girls, Helen (12) and Ruth (10). The American Colony Civic Association of Bellerose praised and commended the two pilots for their self-sacrifice. Neither plane crashed directly into homes. Many of the airmen lived in similar communities outside the boundaries of Mitchel Field and were probably aware of the schools, hospitals, and concentrated homes below their training courses. |

|

At the very least they were aware of the inherent dangers their profession imposed upon themselves and the multitudes above which they flew. Both pilots evidently remained at the controls until the last second, fighting to steer their disabled craft away from the houses below to avoid civilian casualties. A fund was set up by the Association to erect a flagpole and small Memorial Monument at the site of Bylander’s crash on the “mall’ at 239th Street.

Little Neck American Legion Post 103 members also investigated the accident preparatory to erecting a new, second, larger memorial to include the 11 airmen’s names, along with historical context and background in an appropriate companion interpretive display. The consensus amongst the Legionaries and most officials and researchers, me included, is that “the crews had enough control, however slight, to deliberately and successfully crash their ships into the two streets in a conscious and deliberate effort to avoid civilian casualties.” (AL Post 103) It is indeed a miracle that neither plane crashed directly into houses and seems like divine providence that the two pilots somehow managed to guide their severely compromised aircraft into open spaces amongst the crowded homes. Post 103, with the help of many local political and community leaders, have also initiated the nomination process for posthumously awarding the eleven airmen the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for their life-saving action that day. SInce January of 2018, American Legion Post 103 spearheaded by Jim Buccellato, began working on a project to erect a more suitable memorial to the 11 airmen and 1 civilian killed in the accident which will include their names along with an appropriate inscription. Their effort was somewhat hampered by the pandemic, but they succeeded in raising the full cost of the Memorial (fabrication and installation) of $42,000. The new monument included the original small plaque placed at the location in the 1990s by the local community. AL Post 103 also continues to campaign the government to award the 11 crewmembers the Distinguished Flying Cross. |

The original memorial.

A L Post 103 Monument Committee Chairman Jim Buccellato at the memorial site with a descendant of Lt. Hugh Palmer Bedient.

|

B-18A Plane 9B-45: Burlingame serial # 37-583

1st Lieut. Paul Burlingame, Jr. of Louisville, Kentucky:

2nd Lieut. James Frederick Dow of Houlton, Maine:

2nd Lieut. Hugh Palmer Bedient of Falconer, New York:

Staff Sgt. Martin J. Costello of New Bedford, Massachusetts:

Corp. Thaddius Ted P. Kraszewski of Southampton, New York:

Private Clinton O. Rhodes of Clinton, New Jersey:

B-18A Plane 9B-43: Bylander Serial # 37-576

2nd Lieut. Richard M. Bylander of Little Rock, Arkansas:

2nd Lieut. Paul Moffett Lambert of Lakewood, New York; (Newton Highlands, Mass)

2nd Lieut. James Herbert Hail of Lawrence, Kansas:

Staff Sgt. Claude A. Shelbaer of Hempstead, New York:

Corp. Frank X. Deeley of Daytona Beach, Florida:

1st Lieut. Paul Burlingame, Jr. of Louisville, Kentucky:

2nd Lieut. James Frederick Dow of Houlton, Maine:

2nd Lieut. Hugh Palmer Bedient of Falconer, New York:

Staff Sgt. Martin J. Costello of New Bedford, Massachusetts:

Corp. Thaddius Ted P. Kraszewski of Southampton, New York:

Private Clinton O. Rhodes of Clinton, New Jersey:

B-18A Plane 9B-43: Bylander Serial # 37-576

2nd Lieut. Richard M. Bylander of Little Rock, Arkansas:

2nd Lieut. Paul Moffett Lambert of Lakewood, New York; (Newton Highlands, Mass)

2nd Lieut. James Herbert Hail of Lawrence, Kansas:

Staff Sgt. Claude A. Shelbaer of Hempstead, New York:

Corp. Frank X. Deeley of Daytona Beach, Florida:

|

1st Lieut. Paul Burlingame, Jr.

of Louisville, Kentucky: 2nd Lieut. James Frederick Dow

of Houlton, Maine: 2nd Lieut. Hugh Palmer Bedient

of Falconer, New York: |

2nd Lieut. Richard M. Bylander

of Little Rock, Arkansas: Staff Sgt. Claude A. Shelbaer

of Hempstead, New York: 2nd Lieut. James Herbert Hail

of Lawrence, Kansas: |

2nd Lieut. Paul Moffett Lambert

of Lakewood, New York; (Newton Highlands, Mass) Staff Sgt. Martin J. Costello

of New Bedford, Massachusetts: Corp. Thaddius Ted P. Kraszewski

of Southampton, New York: Photo taken at Mitchel Field |

|

No photos available of, Corp. Frank X. Deeley of Daytona Beach, Florida: Private Clinton O. Rhodes of Clinton, New Jersey: Donations may be made directly to the Post: made payable to: “Little Neck-Douglaston Veteran’s Memorial Inc.” C/O NY State Little Neck-Douglaston American Legion Post 103 42-28 235th St Little Neck, NY 11363 POC: Post 103 Memorial Committee Chairman - Jim Buccellato; 703-625-0181; [email protected] THANK YOU! Sincerely, Paul MartinTo donate directly using your credit card or Paypal, please use our GOFUNDME Link below. |

Mrs. Emily Kraft

Bellerose, Queens |